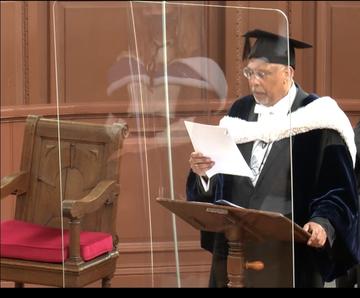

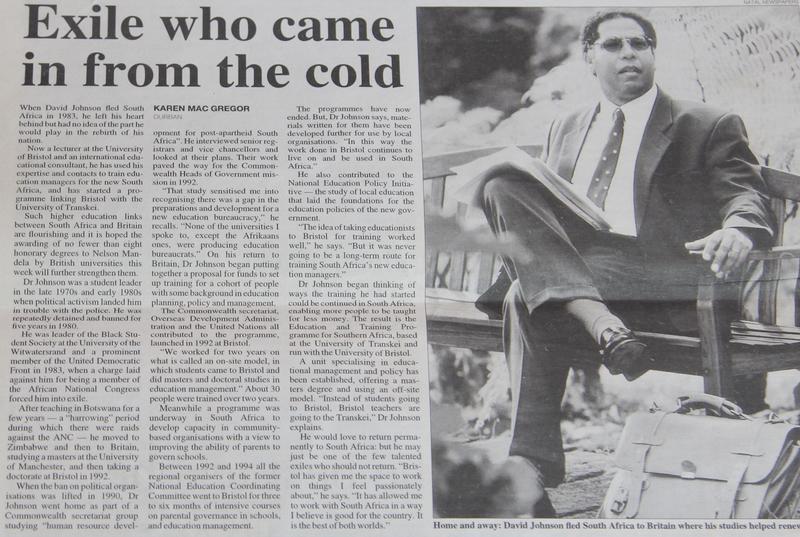

Dr David Johnson: an academic journey

Dr David Johnson, University Reader in Comparative and International Education and Fellow of St Antony’s, discusses his academic journey and the role of Proctor

Dr Johnson, your profile on the University website shows that you took your first degree in South Africa. Would you like to tell us a little about your experiences as an undergraduate?

Thank you for asking. I am, after agonising for many years about whether I should, writing my memoirs, and this helps my recollection.

I was an undergraduate at the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa in the early 1980s. South Africa was still under Apartheid rule. The University of Witwatersrand was a ‘Whites-only’, English-language university, but under Apartheid rules it was allowed an intake quota of Black (African, 'Coloured' and South African Indian) students, not exceeding 10% of its net enrolment.

Black students seeking admission had to satisfy two conditions. First, they had to provide evidence that the degree for which they were seeking admission was not offered at a university that was created specifically to cater for the racial or ethnic group under which they were classified. In my case, being of dual heritage, that would have been the ‘Coloured’ University of the Western Cape. Second, they had to have obtained on matriculation (the school leaving examinations) the grades sought by the University; for African, Indian and ‘Coloured’ students attending poorly resourced and disincentivised state schools, these were notoriously difficult to achieve.

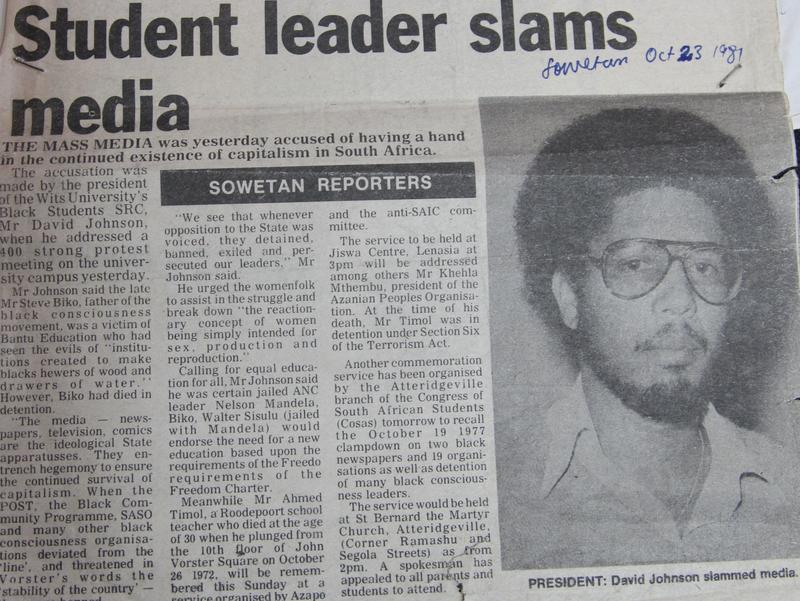

Soon after I began my studies, I was elected president of the University’s Black Student Society. Not all 1,400 Black students who were accepted under the quota system at the time were members, but the majority subscribed to the idea that we ‘studied under protest’. We declined, for example, to use the sporting and leisure facilities the University offered, or to attend its graduation ceremonies. After all, ‘mixed sport’ and other forms of social engagement between racial groups were prohibited in South Africa.

In essence we were all sensitive to the scourges of a deeply divided education system under which many Black children were denied a meaningful education. The Apartheid mantra was of course that education for African children would be sufficient only to their prescribed status as ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’.

In 1976 African students had already protested the injustice of having a language that they rarely spoke foisted upon them as the medium of teaching, together with a racial ideology that insulted their innate abilities. Many were shot and killed and that in turn led to the displacement of many young people, who decided to suspend their education until ‘freedom was won’. They left South Africa in droves to prepare for an armed insurrection.

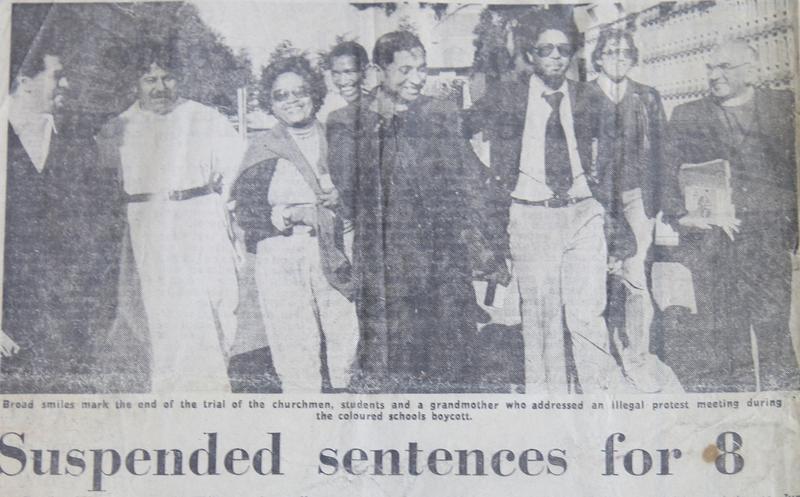

I therefore felt I had a duty not simply to protest injustice, but to advance the ideals of the liberation struggle. In 1980 I instigated protests in schools in Johannesburg that quickly spread nationally. I was detained under the security policy and held for several weeks in solitary confinement in the notorious John Vorster Square police station, and released only to stand trial under the ‘Riotous Assembly Act’ later that year.

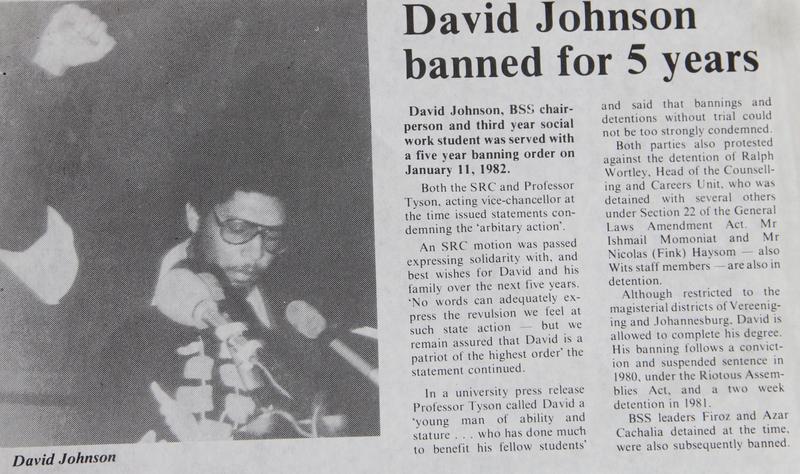

Found guilty, I received a five-year suspended sentence that prohibited me from speaking at open-air gatherings. But not so under the cover of a roof! And so began a series of fiery anti-Apartheid speeches delivered from the University’s Great Hall. In 1981, in a rally to protest Apartheid South Africa’s Republic Day celebrations, I was blamed for inciting students to burn the South African flag. I was detained again, held in solitary confinement and returned to the now familiar routine of being frogmarched in leg chains, in the dead of night, to the torture chambers of the 10th floor of John Vorster Square. It was here that many political activists were murdered by the security police.

I refused to be silenced and was eventually banned for five years under the Internal Security Act (1950); in 1983, after a warrant for my arrest had been issued for ‘promoting the aims of the African National Congress and the South African Communist Party’, I was forced into exile. These events denied me a career in the field of law.

I fled to Botswana, where I worked as a school teacher. In June 1985 the South African military breached the borders of that peaceful neighbouring country and killed a number of political activists, as well as young (white) conscientious objectors who had fled South Africa after refusing to be drafted into the army. I was fortunate. I was attending a National Consultative Conference of the African National Congress in Zambia at the time. Soon after the raid, the Botswana government gave in to pressure from South Africa to expel those ‘targets’ that remained on its list and my work permit was withdrawn. I moved to Zimbabwe, where I taught in a secondary school in Gweru.

How did your journey into an academic career begin?

Serendipitously. My daughter was born in 1986 with atrial septum defect (holes in the heart). We were told later that the condition developed during the pregnancy and could be attributed to the stress and anxiety in the aftermath of the raid on Botswana by the South African military forces. There were no facilities available in Zimbabwe to treat the condition. I was unable to return to South Africa, but my wife and child did. The operation at the Red Cross hospital in Cape Town was a success, apart from (we discovered later) damage to her mitral valve.

In the meantime, the United Nations offered me a scholarship to take up a place at the Victoria University of Manchester, where I read for an MSc in Educational Psychology.

Whilst I was determined to return to southern Africa afterwards, it became clear that my daughter was not thriving and needed further surgery. The operation was carried out at the Alder Hay children’s hospital in Liverpool, and we were advised that she would need more surgery as her heart expanded as she grew older.

I read for a PhD at the University of Bristol and was appointed to a lectureship in 1991. After the collapse of the Apartheid system, I returned to South Africa to undertake a study on behalf of the Commonwealth Secretariat into ‘manpower’ development for a post-Apartheid South Africa.

The report was adopted as a broad agenda for a renewal of public services and an equalisation of the racial distribution of skills; since I was particularly keen to see a transformation of the educational system I developed an educational policy programme for a new non-racial bureaucracy. I extended my interests into educational management and reform in developing countries, and worked in many. In 2003 I was appointed to a University Lectureship in Oxford, with a Fellowship at St Antony’s College.

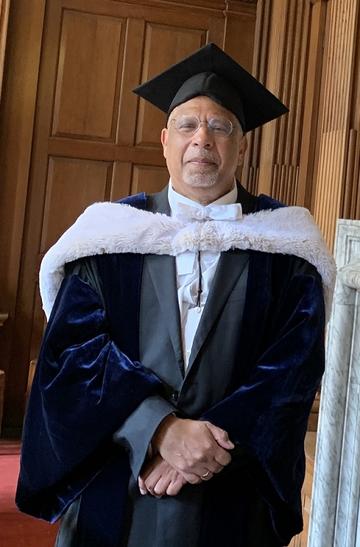

How did you become a University Proctor?

Since my arrival in Oxford I have served my college in various positions: as Dean and Tutor for Admissions for four years, as Senior Tutor for two years, and recently for two years as sub-Warden. St Antony’s was invited to elect a Proctor in 2009. I was nominated to stand at the time but as there were other interests, I withdrew. I am very pleased that a second opportunity presented itself.

The Proctors’ roles are rotated across the colleges. Every year, three colleges each choose one of their Fellows to serve for 12 months; two colleges choose the Proctors and the third the Assessor.

Can you explain what the role of the Proctor involves?

There are essentially three main functions. First, there is an all-important scrutiny function that enables us to ensure that the committees of the University function with integrity.

Second is a disciplinary and welfare element that enables us to safeguard academic freedom whilst ensuring that views, however strongly held, are expressed within the boundaries of the University codes of conduct and that actions, whether in protest at or support of views, are carried out with regard to the physical safety and emotional security of others.

Third, Proctors have a ceremonial function that includes the conferral of degrees. The office dates back to 1248 and ever since, Proctors have walked the streets of Oxford in sub fusc and distinctive gowns. In bygone days, Proctors had police powers and dealt, sometime brutally, with student conduct.

While we do still impose fines for breaches of the code of conduct, or consider rustication or expulsion in serious cases, the severity of our powers has decreased over time – but not so the investigative work necessary to ensure that individual freedoms and rights are protected, and that students are treated fairly in examinations.

The Proctors each year are served by a team of exceptionally competent and hardworking staff who plough ceaselessly through complex and often emotionally draining casework. The Proctors never feature in ‘Inspector Morse’, but the intrigue of much that shapes the way in which we interact in the University would certainly have been worthy of a few episodes.

How are you finding your time as Proctor?

I am very much enjoying every aspect of the role. I am impressed by the wealth of expertise in our committees and the depth of commitment to issues that are discussed; I am also impressed, but never surprised, by the brilliant thought-leadership the University benefits from, and how this is scaffolded by the excellence of our professional and administrative functions.

It is true that many global events over the last few years have increased the urgency of the University’s need to look carefully at itself. At how it measures up to the challenges of equity and equality – as a norm rather than as a numerical target; at embracing pluralism as the national appetite, even by a small margin, is for a return to singularity; and at protecting truth in scholarly endeavour even as threats to subvert academic freedom increase.

There are many things that will continue to test us – from debates about earnings and the costs of living, the value of pensions and security in ageing, and whether we can put a marker on how finite our contribution to intellectual enterprise is, as we know more and get better at what we do. But howsoever these tensions reduce, we can be certain that it won’t be through apathy or a lack of care.

What do you think are the particular challenges for today’s students?

There is an enormous amount expected of young people today, and along with their academic studies there is much on the global agenda that our students feel strongly about.

It’s great that our students are eager to get involved with the big questions of today and the issues they care about. I do worry, though, about where the locus of control lies in respect to some of the debates, especially those around religion, culture and race, and whether we can do more to build minds unafraid to consider different opinions and, where they are disagreeable, to parry in robust defence – rather than intolerant minds, sometimes signified by actions like dismantling platforms and unplugging microphones.

I worry too about social media and the affordances it provides for harassment, bullying and sowing seeds of self-doubt. It is an enormous challenge for young people today to simply ‘be’ who they are, and to navigate with ease the pathways to ‘becoming’.

What do you consider to be your career highlights?

There are a few, but perhaps the most rewarding was enabling access to public primary schools for children who would, to support their families, otherwise spend all day picking through the trash heaps in the urban slums of Faisalabad in Pakistan.

What are you looking forward to this Michaelmas term?

As ever, to engaging with students and to stimulating and shaping nimble minds in preparedness for the uncertainties of our collective futures.

What is your favourite place in Oxford?

Folly Bridge and Christ Church Meadow. I love watching the bustle of people on the bridge, and the polite jostling of birdlife, rowers, punters and longboats for a share of the waterways.

What do you do to relax?

After a walk, having a quiet pint at my local with Woody the golden retriever. And when I can, taking in the odd re-run of an episode of Columbo, the cunning American detective.