Bry's Diaries (part one)

Meet Dr Bryan (Bry) Wilson, coral biologist in the Department of Zoology, and Oxford’s own intrepid explorer

Bry and his colleagues have been carrying out some crucial research on coral reefs in the Chagos Archipelago, an enchanting, endangered corner of the Indian Ocean.

Swinging out of my bunk onto the floor below, I weave foal-like to the closed porthole, unscrew the tarnished brass restraining bolts and swing it open. A foamy deluge slams into the window and I peer through the foggy glass, seeing nothing but dark chaos and violence outside.

We asked him to record a few diary entries of his recent trip, and it’s a great privilege to be able to share them here – we'll add a few more in January too. They only contain a glimpse of Bry’s important work though, so if you’d like to find out more, why not drop him a line – he's on Twitter right here.

I – Journey to the Great Chagos Bank

I’m Bry Wilson, a coral biologist in the University’s Department of Zoology and Stipendiary Lecturer in Biology at Jesus College, and in a year that has seen overseas fieldwork relegated to the halcyon pre-pandemic days of yore, I’ve just begun my first international foray since the chaos that overtook the world, returning to the oceanic sites that we were forced to abandon almost a year ago to the day...

The last weeks and months of expedition planning have been a strange new territory for me – one of seemingly endless form filling and in-depth risk assessments for a trip that never quite seemed like it was actually going to happen. Finding myself strapped into a plane seat and hurtling down a runway at Heathrow last weekend was a surreal moment, a very normal thing made bewilderingly abnormal. As one of the first researchers to venture forth from the University since international travel restrictions were imposed, there was something of a trailblazing, pioneering feel to it all.

Our expedition crew have been gathering in Male, the capital city of the Maldives, but it’s an unspoken rule that the annual Chagos Archipelago adventure doesn’t officially start until we’re all aboard the good ship Grampian Frontier and have hauled anchor.

All told, we’re an eclectic group of thirteen researchers spread across nine institutions (the University of Plymouth, Lancaster University, the Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences, Stanford University, Tritonia Scientific, Exeter University, the Zoological Society of London, Imperial College and, of course, Oxford) working on a diverse range of marine biological and oceanographic fields.

My dispatches will introduce you to these scientists and the very personal passions that drive their pursuit of knowledge in this far-flung corner of the world, as we explore the unrealistically azure waters of the central Indian Ocean together.

Our ultimate destination on this voyage is a remote chain of islands in the middle of the British Indian Ocean Territory, some five hundred kilometres and four days’ sail south of here, a region of innumerable superlatives. At over 640,000 square kilometres – roughly the same size as France, or California – it is one of largest no-take marine protected areas (MPA) in the world, and to us land-centric beings, it seems mostly empty. The land masses of the fifty-eight scattered islands and islets that comprise the Archipelago make up a paltry fifty-six square kilometres, a tiny fraction of the MPA. When first established, the British Indian Ocean Territory MPA effectively doubled the area of global marine protection overnight.

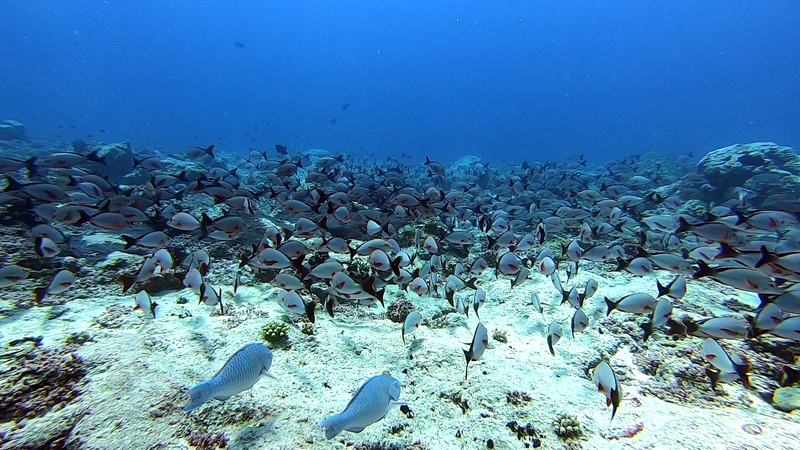

There are over 66,000 square kilometres of some of the best-preserved shallow reefs in the Indian Ocean, if not the world, as well as eighty-six sea mounts and two hundred and forty-three deep sea knolls. In the midst of it all is the Great Chagos Bank, the largest submerged coral atoll in the world. The extraordinary seabird population here is one of the few growing breeding colonies in the tropical Indian Ocean, and the surrounding seas have as much as eight times more reef fish biomass than anywhere else in the region.

The islands are a globally important breeding centre for the world’s largest terrestrial invertebrate, the coconut crab, and the beaches provide nesting sites for up to half of all the green and hawksbill turtles in the region. The area even has its own endemic sub-population of manta rays. Most significantly for me, it is the only home to the world’s rarest – and indeed critically endangered – coral, Ctenella chagius. The seas here are the cleanest waters ever recorded, and the coral reefs are amongst the healthiest in the world. These reefs are the basis of a habitat whose contribution to global marine biodiversity cannot be overstated.

And the overriding reason for this biological significance? Its utter remoteness from humankind. Aside from the US Naval Support Facility on Diego Garcia, the largest and southernmost landmass in the Archipelago, the islands have been almost entirely uninhabited and untouched for over a half a century. In the context of a world subjected to the daily trials and tribulations of unsustainable human development, the MPA presents us with an almost unique opportunity to study the effects of anthropogenic climate change on an ecosystem free of the confounding effects of direct human impacts.

This expedition and the research I’ll be telling you about in the coming weeks would not have been possible without the extraordinarily generous funding of the Bertarelli Foundation. All of this began back in 2010, when the Foundation – along with other NGOs and the UK Government – helped to create the British Indian Ocean Territory MPA. The research work was formalised in 2017, when the Foundation announced its new collaborative and interdisciplinary programme for marine science in the Archipelago.

The programme builds on a series of expeditions, workshops and strategic plans to create a vision for the marine reserve as a global exemplar of science and conservation activities working to support effective management. It comprises a team of researchers from all over the world.

As I write this, several hours out of Male and a gentle southerly swell making the text on my screen swim before my eyes, I’m hoping that the coming weeks’ diving in this incredible underwater environment – of which it is thought we have surveyed less than three percent – will reveal more insights, and yet more questions, about this globally important and utterly unique and iconic ecosystem.

II – Caught in a southwesterly swell

Urgh. Day two and I’ve got that déjà-vu feeling that comes in the early days of every expedition, as alien noises and muffled voices drag me from an oft-broken slumber. Like a newborn lungfish, wide watery eyes struggling to focus in the unnatural darkness of what seems to be a small but comfortable cave, I am deep in the bowels of...somewhere.

There’s something not quite right. I find myself unexpectedly rolling sideways onto my face. I lay there bewildered. Maybe I squeaked. One eye shuttered by the pillow, the other searches wildly throughout the gloom, trying to make sense of it all. A repetitive thunderous booming from below. Or perhaps the side. And then, through the cave wall behind me, as if from far away – Supertramp. ‘Goodbye Stranger’. Followed by muffled shouts of self-encouragement in heavily accented Scots.

Of course – I’m on expedition again. And Donald (the Coxswain) is giving the exercise bike in the ship’s gym next door his Oban best.

Swinging out of my bunk onto the floor below (in a manner that very much suggests I’ve never done this before), I weave foal-like to the closed porthole, unscrew the tarnished brass restraining bolts and swing it open. A foamy deluge slams into the window and I peer through the foggy glass, seeing nothing but dark chaos and violence outside. A day’s sail south along the Maldivian Archipelago and we’re seemingly in the midst of a heavy southwesterly swell, with white horses (the nautical name given to the frothy wave caps in rough seas) suggestive of a middling Force Four to Five. This immediately makes me grumpy, because I’m supposed to be in a balmy, tropical, azure-watered paradise. And not Oban.

It’s a common misconception that tropical seas are a near-constant picture of calm and tranquillity, the water’s surface like a mirror, with nothing to show where the oceans end and the skies begin. Not in my experience. And although I was expecting something like this, I’m still not happy about it.

You imagine that marine biologists never get seasick – and it would indeed be a poor career choice if we did. I have known seasickness, of course, but only twice. When eight years old on a cross-channel ferry in a winter storm, and again, a quarter of a century later, bobbing about in a rough swell, twenty-three metres above the sunken USS Yongala off the Queensland coast, sat on deck in my wetsuit in thirty-four degrees C, waiting for a group of newly qualified divers to kit up. But never since! Sometimes, though, I definitely don’t feel myself and more often than not, it’s on days like today when I have to work – and I’m trying my best to focus on my laptop, confined to the inside of the boat.

The human body has this wonderful balancing system that comprises a pool of liquid in semi-circular canals in each inner ear, with tiny hairs that protrude into this liquid and detect its (and your) movement, acting like a spirit level for the brain. And right now mine’s broken. My ears are determinedly sending out signals that I’m rising and then falling again, a couple of vertical metres at a time, with each long passing swell. My eyes, on the other hand – staring fixedly at a single point on my screen – are busily reassuring my conscious that I’m utterly motionless.

That’s when the nausea kicks in, and I give up any semblance of trying to work and head to the foredeck for some gentle sunshine, where I find our expedition medic, Mister Robert Crawford (already affectionately known to all and sundry as ‘Bob’) sat. I stress the ‘Mister’ because Bob is a spinal surgeon and as such, in something of an historic and arcane tradition, must dispense with the titular ‘Doctor’ (which harks back to centuries ago when surgeons were classed as little more than barbers of the flesh).

In my short time with him, I’ve already formed the opinion that Bob is that wondrous cliché of a professional healthcare worker; calm, quietly spoken and infinitely reassuring. Quite literally the polar opposite of me, and exactly the kind of person you want on an expedition when the nearest medical centre can be a three-day sail away. Bob is a veteran of these expeditions, having accompanied the current team out to the Archipelago in 2018.

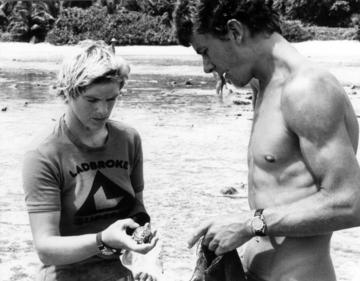

More impressively though, Bob spent five months in 1978 essentially marooned on one of the islands here, only a couple of years out of medical school, as the resident medic on one of the first exploratory science expeditions to the Chagos Archipelago. Bob was at pains to point out that the ‘science’ on this trip seemed to be little more than ‘collecting things and dropping them into jars of formalin’.

Bob Crawford on an earlier expedition

One of the defining experiences of our contemporary expeditions is the routinely inconsistent internet access – but back in the seventies there was only limited radio contact with the ‘nearby’ (several days away) US Naval Support Facility on Diego Garcia (delivered in brisk and clipped military tones), and contact with the wider outside world was by monthly mail drops into the lagoon, along with fresh supplies.

Judging by some of the photos Bob’s showed me, ‘fresh supplies’ seemed to mean crates and crates (and crates) of beer – a ‘dry’ expedition this certainly was not. Toilet facilities were also ‘basic’; when Nature called, expedition members would hike up to the northern end of the island and out on to a gently sloping spit of sand into the water – affectionately known by all as ‘Crapper’s Point’ – where they would squat and do their business.

The major concern was the large batfish, which would school beneath this nutritional bonanza and take hungry bites at one’s lower body. Such was the apparent Pavlovian response to this regular feast that the moment Bob’s luminously white behind would appear at the water’s edge, there would be something akin to a feeding frenzy. He carried a stick to try and beat them back whilst in this ungainly and undignified position.

I silently make a promise to myself never again to complain about our expedition facilities.

It is a joy to listen to Bob. His recollections are tinged with nostalgia – and some sadness, especially when he recounts how very few sharks he now sees in the waters around the Archipelago, when compared with forty years back. And how even then, the otherwise pristine white-sand beaches were littered with lost flip flops, which is something we still see today. And then some...

So lost am I in his stories of a bygone era that I utterly forget that I’m blonde and freckled and sitting out on deck beneath the equatorial midday sun. I rue the fact later that evening, when I’ve taken on the painful hue of ripe nectarine.

Gingerly pulling my sheets up over my burned body, I decide that this day is one that is best forgotten.

III – Further south in the Maldives Archipelago

A deafening crash wakes me during the dark hours of the early morning, the gloom outside framed by the porthole window. Much more quickly this time, I realise I’m still at sea and still steaming south. The black waters outside are still pounding the hull and I wonder whether we’re actually steering through this or just bobbing around like a rubber duck, hoping that good fortune alone takes us south.

Later, eating breakfast at the crew’s table, I mention this unseemly weather, and am met with scoffs and guffaws. I’d never thought scoffing and guffawing actually happened outside of an Enid Blyton novel, but there was definitely scoffing and guffawing around that table. And occasional coarse language. It seems that our boat comes from a fleet of sturdy ships that supports a good number of the North Sea’s oil rigs, encountering what sound like some truly nightmarish weather conditions. Most of this crew cut their teeth in the wild coastal waters of Scotland, so it’s easy to see why the ‘storm’ outside is little more than a ‘wee bluster’ to them.

When asked for tips on how I might become more seaworthy – and quickly – they tell me that first things first, I should be heavily tattooed. I don’t really understand. Maybe that extra layer of ink lowers your centre of gravity in heavy seas? Then slowly, an idea begins to blossom in my head...I’m always forgetting essential snippets of Python and R code in my computational analyses, so it might be helpful to have them scrawled permanently across my forearms, possibly a different coding language on each? Whilst I imagine that I’d be something of a hit in the Silicon Valley bars and restaurants of Palo Alto, I’m not sure how much respect I’d get in the pubs frequented by fisherfolk in Peterhead.

Mould on the roof of the lab

One of the main tasks for today is to check out our new deck-mounted expeditionary shipping-container-cum-laboratory and prepare it for the weeks of marine science ahead. After breakfast, a group of us head out aft to the ‘lab’ and throw open the door – only to recoil immediately. If you gathered up all the lost and discarded trainers from the route of the London Marathon and then sealed them up in a shipping container in the equatorial heat, occasionally opening the door to throw a bucket of water over them, it might produce something like the stench that emanated from our ‘lab’. It had taken a ding to the roof, possibly in transit, leaving it open to the frequent tropical deluges. The floorboards were rotted through; the lab benches distended and buckled, their chipboard interiors swollen to twice their normal size; and a fine soft down of mould carpeted every surface. Not quite how we imagined we would be pushing the boundaries of marine biology in the coming weeks...

Cleaning up the lab on deck

Still, being out on deck gives me a chance to take stock of where we are. Apparently we’re still within the Maldivian Archipelago, but we could be absolutely anywhere, there being nothing but a flat and featureless ocean (if you discount the omnipresent two-metre swell as a ‘feature’) from horizon to shining horizon. And at precisely 11:20am, unbeknown to me and whilst I’m gazing out over the guard rail at those huge empty skies all around, we slowly trundle over the Equator, the ship’s compass briefly reading 00.00.0 N/S, 073.46.0 E...

...and I’m back in the Southern Hemisphere, for the first time since the expedition last March when, essentially cut off from the outside world, we were all too blissfully unaware that contemporary life as we knew it was about to change fundamentally.

IV – The southern tip of the Maldives Archipelago

People say that change is a good thing. I’m usually a huge fan of change, and occasional chaos and disorder. Anything that reminds us that there’s very finite limits to what humans can control, and in that sense, despite all our innovations, we’re not so far removed from the ancestral hominids of prehistory – at the mercy of a strange world that we should go out to meet every day with some trepidation, though we still walk through it as if it is of our own making.

Today, however, change is not good thing. The wind has changed; it’s now somehow even stronger. I’m rocking in my bunk more violently. The crashing waves outside seem that bit more, well, crashing. And the ship is definitely creaking more loudly, every rivet straining to break free. I have to remind myself of those North Sea winter storms and the tattoos I have yet to get. As I think Douglas Adams once wrote, ‘discretion being the better part of valour, cowardice being the better part of discretion’, I valiantly pull my duvet more closely around me and hunker down for what I call a ‘bed day’.

Finished reading the diaries? Talk to some of the people behind them:

- Marine science programme on Twitter: @Marine_Science

- The Bertarelli Foundation who sponsor a lot of this work: @bertarelli_fdn

- Bry’s Twitter account: @marinebryology